Geoeconomics has changed considerably in the second decade of the 21st century. Tectonic movements, not always noticeable on the surface, have been gradually shaking the pillars of the old “new world order” of the 1990s. Originated in the global financial crisis that reached, without permanently displacing, the hegemony of finances in contemporary capitalism, these movements have led to the emergence of new forces in politics on a global scale, many of which question the old order by an even more conservative and authoritarian bias. At the international level, these movements still represent outlines of the questioning of both multilateralism and the quest for liberalization of trade and investment. Protectionism is today a fuzzy sentiment that hovers over discussions of international trade, often brandished by the United States and Europe as a proposal or threat, in opposition to the liberalizing stance that guided the conduct of developed countries until the global financial crisis.

In this context, the resumption of negotiations for the conclusion of a long-standing agreement between the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) and the European Union (EU), which actually took shape in May 2016, is surprising. On that occasion, there was an exchange of offers involving trade in goods and services, investments and government procurements between the two blocs, replacing the previous agreements dated from 2004 and suspended in 2006.

According to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB)1, based on data obtained from the Secretary of Commerce of Argentina, while Mercosur has simplified the structure of its offer, the European Union has taken the opposite way, increasing the number of exclusions in relation to its previous offer. It is important to note that the reach of the offers is tacitly conditioned by the EU, based on the advantages inherent to the greater diversity of the trade agenda, which simultaneously enables the exclusion of products that are more sensitive to local producers.

In addition to the exchange of offers, a document imposing conditions was presented, pointing out the requirements for the effective offers to be valid. For Mercosur, it is essential that the import duty from which the tariff reduction schedules depart consider not only ad valorem tariffs specific to each product, but also their combinations, including the variants by technical standards and the application of entry prices. The European Union, in turn, demands that the export restrictions applied by some member countries of the southern bloc, especially Argentina, be eliminated.

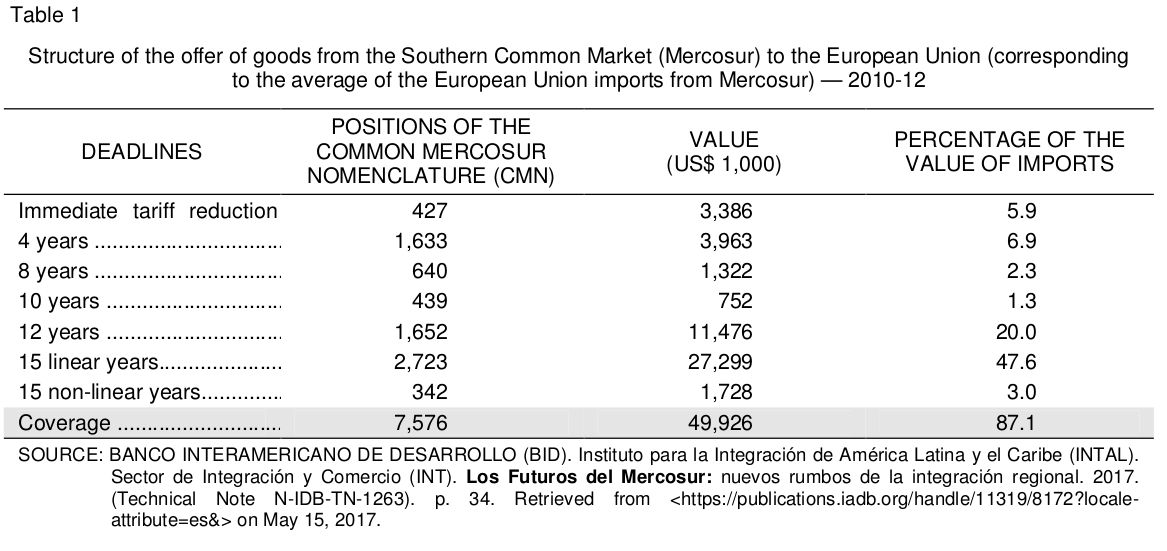

In the 2016 offer, Mercosur’s proposal is structured on seven different deadlines for the elimination of import duties. These deadlines are progressively extended for up to 15 years (Table 1). There is a broadening of the product coverage included in the proposal, bringing the total of products covered by the negotiation from 71% in 2004 to 87% in 2016, which makes it more attractive to the Europeans. This wider coverage is explained by the exclusion of the fixed preference category (products with no possibility of subsequent tariff reduction) present in 2004. In addition, in the current offer, the proposed tariff reduction is linear in 15 years for products corresponding to 47.6% of the average value of the EU imports between 2010 and 2012, while, in the previous offer, the tariff reduction was concentrated in the final years of the 17 years of its extension.

As for services, Mercosur’s offer includes, as a proposal to all member states, the liberalization of the purchase of land in frontier areas and proposals related to the treatment to be given to the employees of European companies. As regards the other proposals in the area of services, each country of the bloc should take responsibility for them. In the area of public procurement, given the lack of a common regime for Mercosur, each country should make its own offer, and only purchases made at the federal level will be covered by Mercosur, with Brazil and Argentina also including purchases made by state companies, which is not the case with Paraguay and Uruguay.

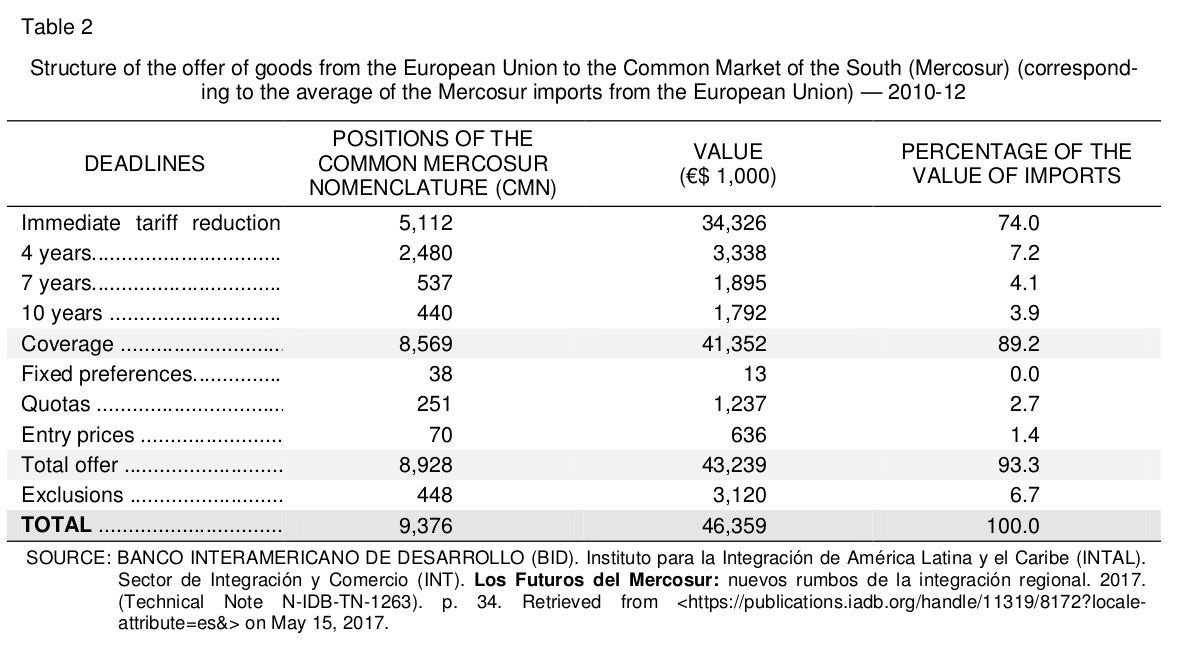

The offer of the European Union kept having a complex structure. Besides the tariff reductions, there are groups of positions subject to fixed preferences, quotas and entry prices (minimum import prices imposed by the EU on certain agricultural products). Although the coverage of the offered items for immediate tariff reduction has increased compared to 2004, the products included there already have, to a large extent, tariff exemption. Another controversial category concerns exclusions. Their number has grown compared to that of the 2004 offer and includes sensitive products, such as beef, ethanol, sunflower oil, tobacco and some types of wine.

In services, the European offer separates commercial services from those involving the presence of technicians and other staff, showing a recent concern with the issue of migration, although showing openness to the inclusion of new services over time. With regard to public procurement, the EU offer allows the participation of Mercosur companies as if they were national. However, it allows member countries to impose limitations on such participation, both in public works and in the purchase of goods and services by the State.

The offers were delivered for internal consultations to the private sector of the member states in each bloc — more specifically to the appreciation of the business federations in each continent —, with pre-scheduled meetings for the continuity of the discussion. The next one is due to take place in July, in Brussels. It is expected that the debate on the final text of the agreement will be concluded by the end of 2017, and the discussion of the offers, in 2018.

This attempt to have an agreement can be analyzed in terms of its perspectives from three distinct axes: the idiosyncrasies of Mercosur, with the recent political and economic instability that has arisen in the bloc, the changes in international geoeconomics, with Trump’s rise to power in the United States, and the point of view of Europe.

Mercosur has undergone great tremors in the recent period in both economic and political points of view. This instability has slowly reinforced Argentina’s position. Macri’s inauguration in the presidency of Argentina in December 2015 marked a change in the country’s position vis-à-vis the regional bloc, elected as its foreign policy priority. In previous periods, Argentina’s position was to hinder the more liberal proposals in Mercosur, especially when Brazil was the protagonist. However, there was a concern not to break the external pro-trade view of the bloc, thus avoiding a closer approximation with Venezuela’s proposal to tighten the intra-bloc ties and strengthen the South-South trade. Its position was, then, marked by some sort of dubiety, which weakened the country’s protagonism.

Macri’s Argentina has revised its old positions, getting closer to the historical positions of Brazil and Uruguay. This allows a greater understanding in the bloc, a situation reinforced by Venezuela’s suspension, which also increases the pressure to speedily address pending issues, in order to demonstrate that the main obstacle to progress lied in the chavista policy.

The existing strategic understanding, reinforced by the change in the conduct of the Brazilian foreign policy, has broadened the common agenda among the member countries, with constant bilateral meetings, despite the political problems present in the various countries. This conjunction of factors explains, from the point of view of Mercosur, the vigor with which the agreement with the European Union was resumed. However, the internal political instability of the countries of the region and the class interests jeopardized by the economic crisis can make it difficult to meet the deadlines. The relative timidity of the European proposal, conditioned by the specificities of the domestic policy, is another factor that may hinder the rapid advance of the proposal from the point of view of Mercosur.

The changes in Mercosur occur in a context of international turbulence. The conduct of the foreign policy of Trump’s administration is another factor that has caused changes in the international negotiations. This is a much more “cultural” change than an effective one, but it has been disturbing the international agenda in an unprecedented way in recent decades and changing the nature of the relations between Europe and the United States.

Trump, elected with a vague protectionist speech, has had many difficulties in putting his ideas into practice. The recent setbacks in proposals that could challenge the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the lack of impetus to put barriers to the entry of Chinese products show that Trump is attentive to the domestic public and the business class of the United States. However, the same caution in the U.S. conduct has not been seen in the agreements still under discussion or at an early stage of implementation. The withdrawal of the U.S. from the Trans- Pacific Agreement negotiations has opened a huge avenue for the consolidation of China’s interests in Asia, which reflects on Europe’s strategy for the region. Moreover, the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Paris Agreement is another element that has shaken the European confidence in the U.S. ability to lead the international agenda. The navigation will have to be made with a greater degree of experimentation, since the captain seems to have retired without leaving anyone in his place.

For the European Union, the North American hesitation in following the agreements widely debated in previous years has been viewed not only with concern, but also as a source of opportunities for expanding its commercial and political presence. The dubiousness of the U.S. policy opens, for example, the way for Europe to retake interest in the agreement with Mercosur, at a time when the change in the Brazilian foreign policy seems to be inclined toward promoting a preferential agreement with the United States.

The European Union also has its own political ghosts to face. Macron’s election in France has given a new breath to the bloc, shaken by the result of the British plebiscite that led to Brexit. The constant terrorist attacks have turned the fight against immigration into an inescapable theme in the domestic policy agenda of the member states. Extreme nationalism, though defeated in France in the second round, has gained political strength and can no longer be ignored. This has limited the potential of the external agenda of the bloc, while there are pressures for local and national populations to be heard in the decisions of the European Union. As an example, the European Commission decided, on May 16 this year, that the broader trade agreements should be ratified by the 33 national and regional parliaments of the 28 countries that make up the bloc. If not amended, this decision suggests a broad agreement like that one between the European Union and Mercosur might come into force any time between five and 10 years from now if it is not definitively hampered by any of those parliaments.

Seen from a broader point of view, what seems to be at stake in this impasse is the growing lack of social legitimacy of purely commercial agreements. These negotiations have always been a mere institutional framework to legitimize the interests of the larger companies in areas such as trade, investment and protection of intellectual and technological property, with a negligible positive impact perceptible to the citizens of the countries involved. Agreements that effectively involve populations are increasingly necessary for the political legitimization of these decisions in a world of information, so as to bar the return of a nostalgic nationalism. In this sense, although efforts to retake mutual understandings should be praised, the proposals concerning a trade agreement between Mercosur and the European Union can be understood as an anachronism in this second decade of the 21st century.