Brazil’s largest company and one of the world’s oil giants, Petrobras has shifted in recent years, from a guarantor of the country’s future into an outstanding representative of the set of frustrated expectations that accompanied the end of the economic growth cycle achieved between 2004 and 2010. The discovery of huge oil reserves in the pre-salt layer, in a background of rising oil prices at the international level, has brought the prospect of a thriving future, in which energy autonomy would prevail along with surplus in the balance of payments, industrial and technological development and reducing regional inequalities. Thus, as a company partially owned by the state, Petrobras would assume a leading role in national development. Today, the “pendulum” has swung the other way, and expectations are more modest and sometimes even pessimistic. The euphoria of the 2000s led to the implementation of projects that, in light of the current scenario, have proven to be unrealistic regarding timing, costs and long-term assumptions. This fact, along with plummeting oil prices, the adoption of a controversial pricing policy and the revelation of corruption scandals, has weakened the financial position of Petrobras, and helps to form an underrated perception of its importance for the country. Despite the crisis, Petrobras still matters, in both economic and strategic terms for the development of Brazil.

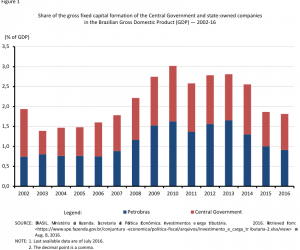

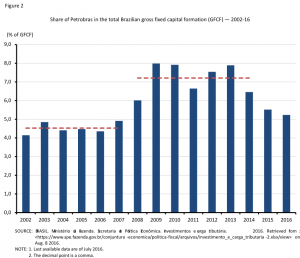

The investment carried out by Petrobras is an important part of national investment. It currently corresponds to more than 50% of the gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) of the Central Government and state companies, which has increased from 2008, not due to the reduction of other investments of the government, but to the growth of both figures as a proportion of the Gross Domestic Product (Figure 1). On average, between 2008 and 2014, investments of Petrobras represented 7.2% of the total Brazilian GFCF, compared to 4.5% between 2002 and 2007 (Figure 2). Excluding residential construction, which accounts for approximately 20% of the gross fixed capital formation in Brazil, oil-driven investment now represents about 9.0% of the total national investment in the construction of buildings and non-residential structures, machinery and equipment, and intellectual property products.

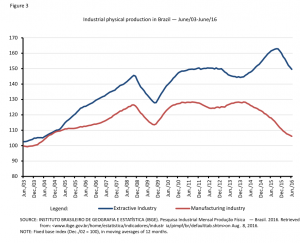

The growth of investments in oil and gas exploration can be seen in the dynamism of some indicators, including the production of the extractive industry. In Figure 3, whose data were based on December 2002, we notice that in the period until June 2016, the physical production of the extractive industry accumulated a growth of about 50.0%, while the manufacturing industry expanded less than 10.0%. It is true that part of this growth can be attributed to the increase in iron ore extraction, which was also favored by rising prices seen until mid-2012. This assertion does not lessen, however, the relevance of the oil and gas extraction activity for the performance of the sector, which accounts for the largest share of the extractive industry (65.0% against 30.0% of iron ore).

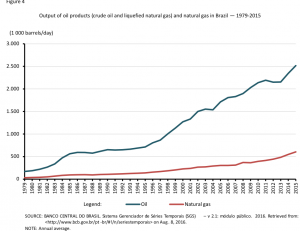

From the mid-90s, the domestic output of oil and gas has started an accelerating growth trend (Figure 4). Currently, oil production is at 2.5 million barrels per day, representing an increase of 98.0% since the early 2000s, while natural gas is at 600 thousand barrels per day, an increment of 165% in the same period. At the same time, the share of oil processed in domestic refineries increased from 80.0% in 2010 to 88.0% in 2016. Since the early 2000s, the volume of oil processed in domestic refineries has significantly increased about 20.0%, though not proportional to the increase in production. Finally, the expansion of oil and gas yield has favored the Brazilian external accounts, though not exclusively, since both the recession and the reduction of prices in the international market have also contributed to the expansion of trade surplus. Reflecting the interaction of these three facts, trade deficit of fuel was reduced from US$14.6 billion in 2014 to US$5.4 billion in 2015 and to US$0.9 billion in the first four months of 2016.

Although still resting on a solid production base, Petrobras is currently facing evident difficulties, especially regarding its financial health. New and relatively modest prospects for the evolution of global demand have led to a rescheduling of the plan of production expansion and to the adoption of more realistic premises for the future behavior of variables such as the exchange rate and prices. In the Business Plan of June 2015, released still during the presidency of Ademir Bendine, it was estimated that oil production should reach 2.8 million barrels per day by 2020, a significant reduction from the forecast in the previous plan of 4.2 million barrels per day. This is not, however, an exclusivity of Petrobras. There has been a broad trend of moderation in the pace of production growth. In the new plan, the forecast for world production growth was 1 million barrels per day by year 2020, while in the previous plan it was 1.6 million barrels per day for the same period.

The combination of a scenario involving the assumption of more moderate prospects for production and prices with the excesses of the recent past and, above all, the high amount of investment necessary to explore the pre-salt has increased the leverage of the company and its financing costs. This fragility has induced the development of a plan of asset selling and the review of investments in order to reduce debt and focus efforts and resources on the exploration of the pre-salt. With regard to divestments, in the January 2016 revision of the Business Plan, Petrobras expected to dispose of assets amounting to US$15.1 billion between 2015 and 2016 (reaching only US$0.7 billion in 2015) and US$42.6 billion between 2017 and 2018. Such a measure would help to reduce the company’s net debt, which exceeds US$100.0 billion. It was estimated that investments would amount to US$98.4 billion between 2015 and 2019 (a cut of US$32 billion compared to the previous plan), focusing on production and exploration activities. Applying the current exchange rate of about R$3.3/US$, this amount would be equivalent to an annual average investment of R$80.0 billion, slightly higher than the average of 2011-15 (R$72.0 billion).

Thus, the share of Petrobras in the domestic investment may continue to decline, while the proportion of exploration and production activities in terms of its composition may increase, to the detriment of others, such as the refining capacity, which had been growing in recent years. With the new presidency of the company, further adjustments are expected. However, the expectation is to maintain the general stance of leverage reduction, investment focus on the pre-salt and moderation in projections. Despite the reduction of oil prices in the international market, which seems to be structural, there are indications that the current level is still sufficient to enable the exploration of the pre-salt. In the event of a new round of falling prices, this strategy would also be at stake.

The new scenario for oil prices, besides the induction of a strategic review in investments, also calls into question the pricing policy that has been traditionally conducted by Petrobras. The policy consists of preventing the immediate transfer of external oscillations to the domestic market, with the intention to reduce volatility and indexation of national prices. In this strategy, the transfers occur only when the changes in the level of international oil prices prove to be lasting. This definition includes, in any case, some degree of subjectivity. In 2012-14, due to the persistence of a high level of prices in the international market, the containment of transfers appears to have been extended for too long (Figure 5). Furthermore, in 2015-16, the policy that keeps fuel prices high in the domestic market, even in light of lower prices in the international market, seems to complement the strategy of financial relief — even if not explicitly — by compensating losses from the previous pricing policy, which are almost zeroed, and expanding funds in the short term.

Petrobras’ twofold character, at the same time a public and a state-owned company, imposes the challenge of balance and reconciliation of market and state strategies. The reconsideration of the operating model of the pre-salt exploration system, which discharges the company from the commitment to operate in all fields of these reserves and, at the same time, preserves its preference for those considered strategic, can meet these requirements, provided that, and this is important, the prerogative is actually exercised. Inflated by the favorable situation, the profit of some projects seems, in fact, to have been overestimated. In this context, having to lead the development of all fields could end up burdening the company and reducing the growth rate of investment. A similar occurrence can be observed in the national content policy. Even in the case of an instrument that is widely used by oil producing countries to stimulate industrialization and technological catching up, the national content policy raises the possibility of loss of competitiveness in a scenario of narrower profit margins.

However, if adherence to ambitious projects implies, in the current situation, non-negligible risks, the complete relinquishment of the use of oil as a strategic resource also does not pose as a solution. As a state company, Petrobras still plays the role of stimulating projects that, in a background adjusted for lower prices, meet the interests of the country. This task transcends continued leadership in the exploration of the most robust resources. It also involves the allocation of knowledge and capital accumulated by the company to fulfill broader interests, including the fostering of renewable energy production, the generation of innovation and the narrowing of regional inequalities.