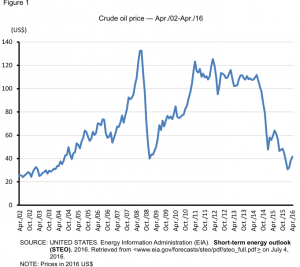

After a ten-year upward cycle, oil prices fell sharply since July 2014, in a move that turned the previous cycle upside down. Even though the commodity’s value has recovered a small portion of these losses in the past months, the speed of the fall is still noteworthy, mostly because it was not anticipated by leading analysts and specialized agencies. Soon after that, it was suggested that the price had fallen due to the slowdown of the global economy (especially China), which caused a decrease in oil demand in a context where the oil supply was growing (Figure 1). However, these assumptions, although empirically true, do not take full account of the situation, which presents itself more multifaceted, with roots that go beyond the relation between supply and demand.

When one reads about the oil price dynamics, it often happens that only the amount demanded by consumers and the one offered by producers, as well as the level of its global stocks, are considered. In this sense, every time there is an imbalance in one of the factors in question, there would be a change in prices in order to restore market balance. It so happens, nonetheless, that historically the oil price trajectory is not fully consistent with the behavior of its demand, at least in terms of its amplitude. Therefore, we must go beyond textbook explanations in order to try and understand this process, for oil is viewed as a national security asset by most countries, giving it a leading position in the global economy. Thus, in our understanding, the geopolitical dispute over the property and exploration of oil reserves is paramount to any evaluation of the subject.[1]

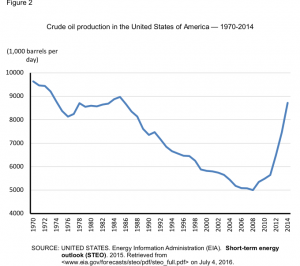

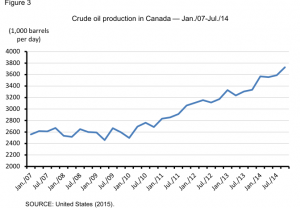

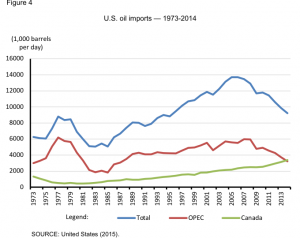

The main factor of oil market transformations in the last years is directly related to the increase in exploration of unconventional resources, which made possible the recovery of the oil and gas industry in the United States (Figure 2) — which had been declining for decades — and the boost of oil exploration in Canada (Figure 3). With the “Shale Revolution” and the growth of oil sands, the United States was able to cut back its oil imports, notably the oil produced by members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). That is an extraordinary situation because it reverses a pattern of growing energy dependency in the United States, which had been putting the world’s most important economy in a position of relative subjection to the OPEC. So, insofar as China’s demand for energy resources increased, there was an escalating fear that there would be an oil shortage in the U.S. eventually, and that feeling naturally pushed prices and speculations upward.

The viability of unconventional resources was only a reality after years of high oil prices, given its high break-even[2], as well as a set of technological innovations (fracking[3], 3D geological mapping and horizontal drilling). Throughout this period, however, there were growing fears that the world was approaching the “peak oil”, once the oil consumption of emerging countries kept expanding, in a background where most oil reserves were already declining. In a context of financialization of commodities, such fears made oil prices skyrocket, since this resource seemed close to extinction. Nevertheless, in a clear paradox, it was precisely this background — theoretically inauspicious — that made possible the oil and natural gas production in new regions in North America, contradicting analysts’ and policymakers’ forecasts[4].

Among the most important consequences of the rise of unconventional resources, we should highlight, first of all, the resurgence of the U.S. oil industry, which grew by 74,42% in terms of total volume between 2008 and 2014. Moreover, in that same period, there was a 36.71% reduction in oil imports in the United States. Thirdly, there has been a significant change when it comes to energy imports by the U.S.: in 2008, OPEC countries accounted for 55.35% of that total, while Canada was responsible for 19.99% of that amount. In 2014, however, the two were virtually the same, since OPEC’s slice represented 40.82% of that total, versus 39.32% of Canada. Lastly, in these years, the boost of Canadian oil production (roughly 1 million barrels/day) coincided with the increase in Canadian oil purchases by the United States (Figure 4).

In light of the above, it appears that the recent drop in oil prices has succeeded the sharp reduction in U.S. energy dependency. It is much more than an oil surplus in international markets and a decline in consumption; it is a major transformation, as the most important global power (the main consumer and importer of oil) seems on the verge of easing a problem that, up until now, was worsening. Given the importance of oil, both economically and militarily, it is not difficult to understand why the decreased need of energy imports from OPEC is a relief for the U.S. government and consumers. Certainly, in an already favorable context, the cooling of world demand may also have contributed to the decrease in price, but it does not explain, by itself, the phenomenon as a whole.

For the United States, energy security is not only about the supply of energy resources at its disposal, but the guarantee that the energy flow to its allies is not interrupted. In that sense, it is clear that the “Shale Revolution” has brought two major consequences that can alter the European energy market. First, the reduction in U.S. imports of natural gas (mainly from countries such as Algeria and Nigeria) makes it possible for European countries to purchase energy from those economies. Due to the fact that the region is highly dependent on Russian energy imports, the emergence of new suppliers may reduce its vulnerabilities by curtailing Russia’s bargaining power. In addition, due to the recent abundance, the natural gas market is saturated in the United States, so that the U.S. government has authorized energy exports to Europe, which could also diversify its options.

When oil prices began to plunge, it was suggested that the movement represented a Saudi maneuver to harm Iran and Russia, its political and energy rivals, and to derail the production of unconventional resources, mostly in the United Sates. This perspective gained ground because, as oil prices plummeted, Saudi Arabia not only did not cut its production, but increased it slightly at first, and then stabilized it in subsequent months. Given the importance of the swing producer[5], it seemed only natural to speculate about Riyadh’s real intentions, although no official statement in that direction has been released. Notwithstanding, as much as this explanation is internally consistent, it is necessary to note some aspects that show how complex and multifaceted the subject is in order to understand that Saudi Arabia may not gather the means to control the oil market that way.

When put in perspective, Saudi energy policy has consistently kept a pattern of caution and fear about sudden changes regarding oil. In the 60s and 70s, for example, the country acted carefully as its neighbors demanded an oil embargo on Israel’s supporters. In the 80s, when oil prices were low, OPEC members pushed Saudi Arabia to cut its production, as it did, but had their expectations dashed, once those cuts were offset by increases in regions outside OPEC, keeping prices low and diminishing Saudi’s market share. Moreover, at the beginning of this century, when high prices benefited Iran and Russia, there was no effort in Saudi Arabia to increase its production and plunge prices. As a matter of fact, Saudi energy policy has been much more reactive then active, and more cautious than bold.

Saudi Arabia has indeed already declared its interest that oil price be maintained at modest levels, a position that sets it apart from other major oil producers. Nevertheless, even if Riyadh is taking advantage of this beneficial circumstance, it would be an extrapolation to state that there is intentionality behind this process. Saudi Arabia is the only state that has vast proven yet untapped oil reserves, but the fall in oil prices was not preceded by a Saudi announcement that showed willingness to expand its production significantly. It was not the expansion of production which anticipated the collapse in prices, but quite the opposite: only after the oil prices began to drop, Saudis increased mildly their own production. More than a plot, it is a strategy that seeks to not repeat past mistakes and to transfer costs to its rivals. From the point of view of the Saudis, if production cuts are necessary to stabilize prices, they should occur elsewhere.

In the current situation, unconventional resources seem to have mitigated energy vulnerabilities in the U.S. and Europe, and apparently have debilitated the political sway of major producers, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia. However, it remains unclear how long this is going to last. Due to its high break-even, the unconventional resources industry is going through a hard time, as shown by investment cuts and underproduction. Despite these problems, so far, most shale companies did not go bankrupt, even if the smaller ones are in a dire situation, which shows that their resilience may be greater than expected. Still, the persistence of low prices may reverse last years’ expansion. In that scenario, U.S. energy dependency would once again be an issue, and that would reposition the geopolitics of oil in favor of Saudi Arabia.

[1] With the increasing financialization of natural resources, the economic and geopolitical movements tend to be amplified, which can affect prices in both volatility and trend.

[2] The break-even is the point at with the income from sale of a product or service equals the invested costs.

[3] Fracking, a slang term for hydraulic fracturing, is the process of creating fractures in rocks and rock formations by injecting specialized fluids (a mixture of water, sand and chemicals) into cracks to force them to open further.

[4] In A mudança na tendência do preço das commodities nos anos 2000: aspectos estruturais (2013), however, Serrano points to an opposite relation: when oil demand started to grow, OPEC did not raise its production to the same level, and the “new production” that came eventually was actually from regions whose production costs were higher, thus establishing a new break-even for this activity.

[5] Swing producer is a supplier of a close oligopolistic group of suppliers of any commodity that controls its global deposits and possesses large spare production capacity.