The attenuation of the increase in greenhouse gas emissions by anthropic action, which is one of the main causes of climate change, is one of the main global debates today. In recent years, there have been major worldwide institutional developments, in accordance with one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (UN)[1]. Despite the broad consensus among scientists and organizations about the causes and possible consequences of climate change, several factors explain the political contradictions surrounding the issue, for instance: the discrepant socioeconomic configurations between societies, the recent disengagement of some rich countries which emit high levels of greenhouse gases (GHG), mainly carbon dioxide (CO2), and the lack of effective mechanisms to identify violations and punish their perpetrators.

Although the discussions on the need for environmental protection have accompanied human history from the beginning, only in the 1970s the issue started to be faced in a genuinely global way, after the Stockholm Conference (1972) took place. Since then, the World Meteorological Organization, a specialized body of the UN System, has been increasingly relevant. This trend culminated in the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in 1988, whose goal is to provide scientific research for the international negotiations on the topic.

There are currently three main provisions that stipulate norms and standards to mitigate global GHG emissions, namely: the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. The UNFCCC was one of the outcomes of the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, which is the official designation of Rio-92. Since then, the countries that signed that instrument have held annual meetings, the Conventions of the Parts (COPs), which are the main decision- making bodies under the agreement and aim at advancing the most substantive discussions on the subject. In November 2017, the COP-23 will take place in Bonn (Germany).

One of the guidelines of the UNFCCC is the notion of “common but differentiated responsibilities”. It recognizes that the more industrialized countries should bear a significantly greater burden to mitigate the problem, given their historical CO2 emissions. Two special lists of countries have been created, Annex I and Annex II, which were given additional attributions. Annex I encompasses the “industrialized countries”, including Central and Eastern Europe “transition economies”. In the year 2000, all these nations should have maintained emissions below the level recorded in 1990. They were also required to submit annual reports on their national policies to the Convention. Annex II countries, all of which are included in Annex I, should also allocate funds to finance projects to minimize climate change effects in developing countries and facilitate technology transfer to the latter. Developing nations, which are absent from both lists, are also expected to submit reports, but less frequently and with more generic targets than those specified in Annex I. The agreement also gives special attention to ecological problems in less developed countries[2].

The second pillar of this regime — the Kyoto Protocol — was established in Japan at the 3rd COP, in 1997 (in force since 2005). Through this protocol countries commit themselves to pursue reductions in emissions through binding targets, but the differentiation principle between developed and developing nations is maintained. The first emission reduction cycle started only in 2008 and ended in 2012. In this period, the Annex 1 governments complied themselves to reduce GHG emissions in 5% in comparison with the 1990 levels. The second period, decided at COP18, in Doha (Qatar), shall take eight years, from January 2013 to December 2020, with targets of 18% below the 1990 levels. In addition, the Protocol provided three flexible mechanisms: international emissions trading[3], clean development mechanism (CDM)[4], of which Brazil was one of the sponsors, and joint implementation[5]. In general, the parties of the Kyoto Protocol have been relatively successful in achieving the goals of the first cycle. One of the main reasons is the sharp reduction in the emission levels in almost all transition economies in Central and Eastern Europe, given their persistent economic difficulties, especially in the 1990s. Russia, which is one of the major global emitters, “managed” to reduce its emissions by almost 30% between 1990 and 2009, while Ukraine cut them by more than 60% in the same period.

The third and most recent pillar of this regime is the Paris Agreement, which has been in force since October 2016. Its main goal is to keep the average global temperature at most up to 2 degrees above the pre-industrial average. An important breakthrough is the provision that all countries, regardless of their stage of development, shall report on their efforts and intentions to mitigate the problems in a more frequent basis, the so-called “nationally determined contributions” (NDC), which thereby has softened the principle of differentiated responsibility under both the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol.[6]

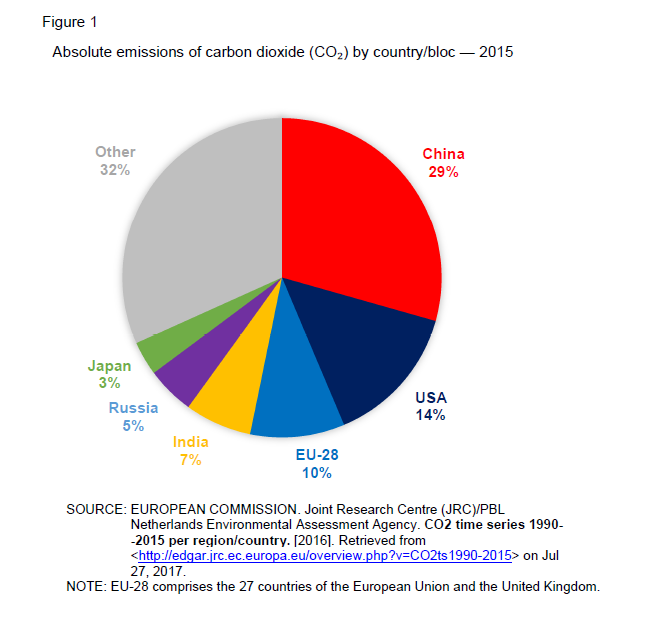

Evidently, the economic, demographic and social differences between the countries fuel the political divergences between them and create enormous difficulties to reach a consensus. When the UNFCCC was signed, in the early 1990s, there were major controversies about the differentiated responsibilities between the developing and the developed countries towards the GHG emissions. To make matters worse, some developing nations, such as China, India and some oil-producing countries, have increased their emissions dramatically since then. China, which has been the largest emitter of CO2 since mid-2000s, currently accounts for almost twice the emissions of the US, the second largest polluter.

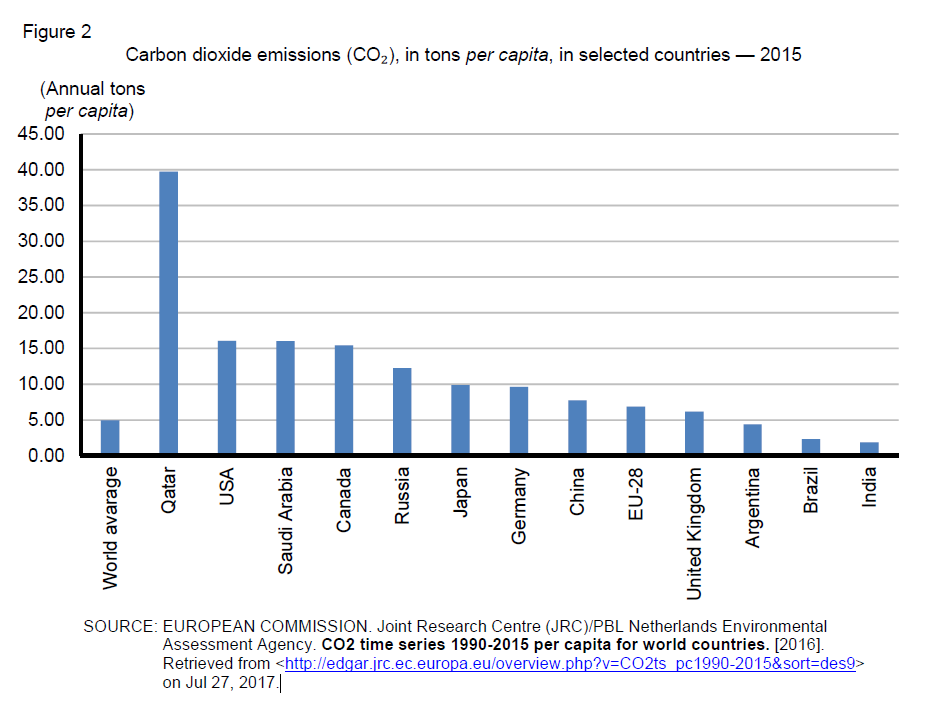

However, as argued by the Chinese, the Indian and even the Brazilian governments, any negotiation on new agreements or targets should always be based on per capita comparisons and on the level of development of each country, as some can afford or are more flexible to invest in cleaner technologies. When we take these parameters into account, the picture becomes quite distinct as regards the absolute emissions. In general, countries that are major oil producers, have high income per capita or are located in temperate regions tend to have higher emission rates.

In this context, the Brazilian government has been historically a supporter of the notion of sustainable development and the principle of differentiated responsibilities between governments. In addition to the general trend of alignment with major emerging nations, the national diplomacy has actively worked with the US to formulate and implement the CDM. In 2015, in its NDC of the Paris Agreement, the nation proposed to curb GHG emissions “by 37% of the 2005 levels by 2025” and “43% below the 2005 levels by 2030”.[7] However, there are still serious doubts about whether the goals established will be achieved by the deadlines set, given the recent increase in the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest (one of the main causes of GHG emissions in the country). Furthermore, some important members of Temer’s cabinet have explicitly expressed their discomfort at the way Brazil participates in the Paris Agreement.[8]

This set of agreements, which has enormous potential for effectively softening global ecological problems, has also created and reproduced important contradictions that may jeopardize the global effort to promote the adoption of cleaner economic growth models. Thus, the lack of periodic revision of the lists of the Kyoto Protocol has generated blatant cases of opportunism in relation to some former “developing” countries. Despite presenting very high per capita income levels and being among the largest polluters in relative terms, the Persian Gulf monarchies remain free from the commitments of the Annex I nations. Moreover, some high emitters have been disengaging from the climate change regime. In addition to the notorious example of the United States, which refused to approve the Kyoto Protocol and, more recently, has sought to detach from the Paris Agreement, other great powers have followed suit. Canada, claiming economic problems, withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012, while Russia decided not to participate in the second round of emission reductions under that treaty and has faced strong internal opposition to ratify the Paris Agreement.

Although the international climate change regime has experienced undeniable progress and has been able to count on increasingly effective monitor and control mechanisms over the last few decades, there is no guarantee that the trend will continue in the same direction. Unlike the previous decades, when disinterest in the issue was greater in developing countries, in recent times, there has been an increase in criticism in richer nations. Unfortunately, the US case cannot be seen as an exception, but rather as a rule. At the same time, countries of later industrialization, such as China and India, have been playing a leading role in the development of a cleaner energy matrix, given the serious environmental problems that their populations have been undergoing.

[1] UNITED NATIONS. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from

[2] The expression “least developed countries” (LDC) is used extensively in the UN system and is updated annually by the General Assembly. In 2016, for instance, it decided that Angola would be no longer considered a LDC after 2021.

[3] It establishes a system of carbon credits based on a logic of economic incentives to promote the reduction of greenhouse gases. The issuing authorities are normally governments (national or local). In short, companies that want to increase their emissions need to buy carbon credits from the government or from other companies that own credits.

[4] It enables a part of Annex 1 countries to invest in carbon cut projects in developing countries.

[5] It allows a given country in Annex 1 to invest in carbon cut projects in another country of the list. In this case, the reduction will be accounted for by the former, while the latter will obtain foreign investments and technology transfer.

[6] THE WORLD BANK. Total greenhouse gas emissions (kiloton of CO2 equivalent). 2017. Retrieved from

[7] REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL. Pretendida contribuição nacionalmente determinada para consecução do objetivo da Convenção-Quadro das Nações Unidas sobre mudança do clima. [2015]. Retrieved from

[8] GINARDI, G. Para Blairo Maggi, metas brasileiras para o clima são só ‘intenção’. Portal Estadão, 17 de novembro de 2016. Retrieved from