Lucas Kerr de Oliveira is an adjunct professor at the Federal University of Latin American Integration (UNILA), Doctor of Political Science and MA in International Relations from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). He is the coordinator of the Center for Strategic Studies, Geopolitics and Regional Integration at UNILA (Neegi) and associate researcher at the Center for International Studies on Government (Cegov), the South American Institute of Policy and Strategy (Isape) and the Brazilian Center for Strategy and International Relations (Nerint).

In an interview to Panorama, Lucas Kerr de Oliveira evaluates the centrality of China in world oil demand and underlines the key variables to understand the sector. He gives his opinion on the economic action strategies of Petrobras and states that the losses of the most acute Brazilian energy crisis in 2001 are still at stake. Oliveira shares his views on the policies of the Brazilian interim government regarding the energy sector and discusses the factors that have exacerbated the economic crisis in the country since 2015, after the fall in oil prices. For our interviewee, rather than an energy resource, oil is a means to boost development and provide security for a nation.

Panorama: For the conventional view, the sharp drop in oil prices is a question of demand, namely, the decrease of the Chinese “appetite” for this raw material. How do you see this matter?

The reduction in expectations of the Chinese growth can be considered a central variable to explain the current dynamics of global energy, including the current cycle of low oil prices, although it is just one of the many variables involved in this process. First, it is worth mentioning that China has increased its share in world energy consumption over the past three decades, standing as the largest global consumer of energy since 2009, when it surpassed the total consumption in the United States. In 2013, China surpassed the consumption of all Europe and the former Soviet Union combined, including Russia. Currently the Chinese energy consumption corresponds to 23% of the total consumption of world primary energy and should reach 25% by 2035. In other words, for the next 20 years China will match the same fraction of world energy consumption that the U.S. recorded between 1980 and 2000. From 1990 to 2011, China quadrupled its total primary energy consumption and also quadrupled oil consumption, reaching almost the same growth rate in coal consumption. From 2013 to 2014, we already noticed a reduction in the growth pace, thus averaging just over 5% a year between 2005 and 2015. In 2015, with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth at 7%, the growth in energy demand in China was only 1.5%, while the increase in oil consumption was 6.3%, representing half of the total global demand growth in 2015, which was 1.9 million barrels. It was expected that China could not keep this pace of expansion forever, especially due to the global economic crisis, which reduced the growth of the major partners of China, such as the U.S., Japan, the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and the European Union. Currently, China accounts for 13% of the world’s oil consumption, about 12 million barrels of oil per day (mb/d), equivalent to just over 60% of the 18 million consumed by the U.S. For all that, China is today a central actor for any scenario projections concerning the growth of global energy consumption.

Moreover, the current international context and the deepening of the political and economic crisis in the European Union largely reinforce the expectations that global energy demand will not expand significantly in the short term, especially as the crisis begins to affect most directly the emerging countries, including the BRICS. In addition, the growing expectations of expansion of oil drilling in new offshore areas (such as the Pre-Salt layer) and the prospects of an increasing share of alternative energy sources to oil, including renewable but also other fossil fuels, such as gas and shale oil, will further extend the prospects for enhanced energy supply in the short term.

Therefore, it is worth mentioning that variables such as demand and supply or inter-enterprise competition are not the only ones that matter to understand the oil industry. Oil is a variable that is directly related to international inter-state competition. This is because the control over the major oil reserves, as well as over the infrastructure of flow, refining and distribution of oil and oil products, consists of an important source not only of income, but also of power and influence for the world’s great powers. Largely, conserving the structures that control the global oil market is directly tied to the political and military influence that the United States still exerts, ranging from the leverage on important countries and oil-exporting regions, to the influence in the decision-making process involving investments in oil prospecting, including the control over the reinvestment of petrodollars, as the prices and sale continue to be held in dollars. And it is precisely the set of key strategic capabilities of the U.S. — the ability to support its allies, to project military force and to settle conflicts — that enables it to control much of the oil sector and the global monetary system. In other words, the political-military power ultimately continues as the main pillar of what still remains of the U.S. hegemony.

Panorama: The regulatory framework of Petrobras combines different strategies of economic activity: it is a publicly traded company, but it is also owned by the Brazilian state (50% + 1). What are the main advantages and disadvantages of such arrangement for the industry?

Petrobras was founded in 1953 already as a partially publicly traded company[1], but 90% of its shares were under state control. The idea of keeping the state as the major shareholder has always been connected to the search for more national sovereignty and autonomy in the exploitation of natural strategic resources such as oil, especially given the need to cope with the pressures and the interests of the largest European and American oil corporations. From the 1950s to the 1980s, such formula was crucial for the effort of Petrobras along the strategy of national energy security, which was shaped to provide logistic support for the major Brazilian strategy, which was based on industrialization and national development. In that process, Petrobras played a crucial role to enable the internalization of the decision-making processes of energy and oil sectors, enhancing the capacity of planning and national control over the exploitation of our own oil wealth. Throughout this process, there has been a slow reduction in the percentage of the state ownership of the company’s shares, but the state continued to be the majority shareholder. Petrobras was fulfilling its historic mission, significantly reducing energy insecurity in the country, diminishing the country’s dependence on imported oil and making Brazil virtually self-sufficient in refining products.

However, in the 1990s, as part of an extreme change in domestic politics, the country abandoned the grand strategy, which until then focused on a more autonomous international integration through national development. In such a context, Petrobras was dismantled, and without any strategic vision, state-owned refineries were separately sold, rather than transformed into a single large unit specialized in petrochemicals. As a result, Petrobras suffered serious restrictions to expand investments and was eventually partially privatized, with shares being sold at a very bad time and well below the actual market value. The result was the reduction of the national state control over Petrobras’ shares to only 32%, compared to a foreign ownership that reached more than 30%.

In this sense, the relinquishment of the energy sector to foreign interests was not restricted to Petrobras, but reached the entire national energy sector, with the sale of strategic infrastructure of generation and distribution of energy to foreign groups. Among the results of the renouncement of these strategic industries to foreign and domestic groups that had no commitment to national development and seek only short-term profit, was the loss of the long-term planning capacity, which is a very important feature in this industry. The ability of taking sovereign decisions on energy matters was handed over to allegedly more “efficient” forces of the market. The most visible outcome of this process was that Brazil suffered the biggest energy crisis in its history, which led to compulsory rationing of energy in 2001, known as “blackout”. The damages of that process are until today a topic of discussion, but considering the impacts then inflicted on industrial output, GDP shrinkage and rising unemployment, we can say that the losses were virtually incalculable.

Since 2003, we have seen a slow recovery of energy planning, which is key for the reconstruction of a national development strategy. The resumption of investments in the energy sector, through the resumption of both the construction of small and large hydroelectric power plants and Petrobras’ investments, was decisive in boosting the economic growth cycle along the following decade. The growth of Petrobras’ investments enabled it to become one of the international giants in the oil industry (peaking as the 4th largest company in the world in 2010), with investments in dozens of countries, besides the recovery of investments in Brazil, making the discovery of huge oil reserves in the pre-salt layer possible.

To have an idea of how important this process has been, it is interesting to note that restoring the capacity to plan and to make decisions in the energy sector has ensured, for example, a high level of oil self-sufficiency. It has also re-enabled Petrobras to use its purchasing power to revive the domestic shipbuilding industry, which has been achieved in less than a decade after the resumption of a minimally planned development strategy. Still considering the energy question, the adoption of local content policies in other sectors, such as wind power, has also been very positive, boosting the machinery and equipment business, such as the wind turbines sector.

Finally, it is interesting to point out that after 2010 the capitalization of Petrobras allowed again the expansion of the state’s share in the ownership of the company (to 46.9%). It ensured the preservation of the investments required to explore the pre-salt layer, which currently accounts for more than 1 million barrels of oil extracted per day. In the same environment, the “New Petroleum Law” has enabled to overcome the limits of the concession system by creating a hybrid system in Brazil, which holds auctions through the concessions system in high-risk areas, but also applies the production sharing system, which it is much more advantageous for Brazil in low-risk areas such as in the pre-salt. The sharing system, by ensuring a 30% share and control of blocks for Petrobras, in fact, means the ability to control the exploitation of national oil wealth, and also the prospects of consolidating the local content policy in the long run.

Panorama: Given the maintenance of oil prices at a low level and the financial difficulties faced by Petrobras, is it possible that this business model will be revised in the near future to ensure greater participation of private or foreign companies?

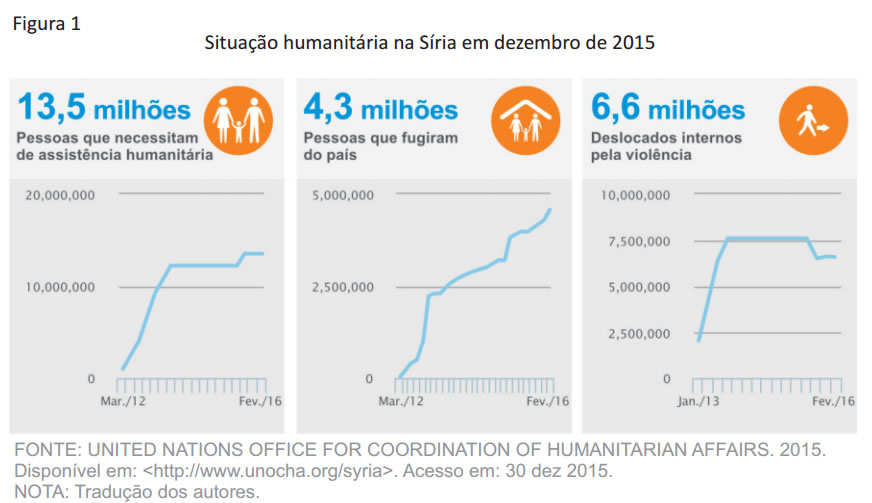

Hardly prices will remain so low for too long. It is more likely that current prices will gradually recover over the next two or three years, as it occurred in the last cycles of significant price drops. However, the timing of that recovery will depend on many factors, namely the pace of resumption of global economic growth, especially in emerging countries such as the BRICS and, also, the increase in the volume of oil consumption in China and the U.S. Another influencing issue is the prospect of change in the export policy of the members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the escalation or the stabilization of the conflict regarding the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran in the Syrian civil war and the western Iraq, involving the Islamic State.

Thus, the cycles of drop in oil prices in 2009-10 and 2014-16 had a significant and direct impact on the investment capacity of Petrobras, which has been even worsened in a context of cuts in government spending and severe political instability. In this context, the weakening of more nationalist policies in energy affairs favors local and foreign antinational sentiments, which advocate the revision of the sharing model and the restoration of the concession system for exploiting the pre-salt. These pressures are already present and integrated into the discussions on the law changes approved by the Senate earlier this year, removing the guarantee of national control in the exploitation of pre-salt blocks, which Petrobras was expected to perform.

Although the current government is interim, thus temporary, there is a clear inclination to proceed with permanent changes, regardless of the negative impacts that may exist. Unfortunately, it seems that an old terminology that summarizes the major lines in dispute on the national political scene in two great antagonistic political and ideological forces still applies: the “nationalists” and the “entreguistas”[2]. The interim government seems strongly inclined to adopt submissive policies in strategic sectors including oil exploration. Among the symptoms of that stance, we highlight the predisposition of the current government to hand over the most profitable assets of Petrobras in an accelerated process of privatization that can cause incalculable long-term damage for the capacity of energy planning of the government, that is, these effects are clearly contrary to the national interest.

Panorama: Some regions of Brazil, which until recently were economically less developed, have witnessed a significant and relatively rapid progress with the activation of Petrobras’ investments throughout the 2000s. In the case of Rio Grande, a city in the southern State of Rio Grande do Sul, the company’s purchases strongly boosted the local shipbuilding sector, which, between 2010 and 2014, hired nearly 7,000 employees. Given the revision of the investment policy of Petrobras, what are the possible impacts for this region, in your view?

Petrobras’ decision to prioritize the acquisitions of ships and oil platforms in the country through a policy of “local content” was primarily responsible for the revival of the Brazilian shipbuilding industry. There is talk of revival because during the neoliberal decade of the 1990s our shipbuilding industry, which was among the five largest in the world in the 1980s, was literally “wiped off the map.” In 2000, what was left of the Brazilian shipbuilding industry employed only about 2,000 workers. In 2003, the administration of President Lula decided to change this situation with the local content policy for purchases of ships and oil platforms for Petrobras, launching the Mobilization Program of Oil and Natural Gas Industry (Prominp). Although the program struggled to raise the percentage of national high-tech content, it was enough to enable the Brazilian shipbuilding industry to rise from the ashes, regaining its position among global leaders, employing over 80,000 workers in 2013-14. Until then, Petrobras kept its accelerated investments and Brazil seemed to avoid significant consequences of the global economic crisis. It is no coincidence that in 2013 President Dilma reached her highest approval ratings, which surpassed those of President Lula.

However, the economic crisis began to affect Brazil more directly from 2015 on. The fall in oil prices, which reached US$ 30 a barrel, has deeply affected the investment expectations of the oil industry all over the world. But Petrobras has been hit harder, and has started to reduce its investments, thus affecting the shipbuilding industry.

Among the factors that have worsened the economic crisis, we draw attention to the corruption scandals involving several politicians of the government coalition and big national companies, including Petrobras and the largest contractors in the country. The judicial operation named as “Operation Car Wash” has provoked the paralysis of the main Brazilian contractors, as well as the interruption of many of the ongoing public works, resulting in a serious crisis over the construction sector of the country, eventually intensifying the economic and social crisis. In that context, we witnessed a strong re-articulation of the opposition with the participation of sectors hitherto allied with the government and the establishment of a serious political crisis. Among the main results, we observe the deepening economic crisis and the political-institutional breakdown that led to the replacement of the elected government with an interim administration.

In this process, Petrobras was constrained to reconsider its investment plans, especially taking into account the unstable political environment and the economic crisis. The interim government has further performed the policy of spending cuts in Petrobras’ investments, foreseeing more significant reductions in future investments. This year alone, the construction of 11 new oil tankers was cancelled, many shipyards went bankrupt all over the country and the production of some oil platforms has been transferred to foreign shipyards. In Rio Grande, platforms that were already commissioned had their contracts cancelled and more than half of the jobs in the local shipbuilding industry have already disappeared. However, the resumption of Petrobras’ investments in the purchase of ships and platforms will depend on both the pace of the recovery in oil prices (which may take about two years to stabilize) and on the outcome of the current political crisis in the country. If the result is favorable to the company and the local content policy, the recovery of investments in ships and platforms should take place in the coming years, that is, it tends to be slower and more gradual than the ideal for the shipbuilding industry.

[1] The Portuguese designation for this kind of corporation is Sociedade Anônima (S.A.).

[2] Entreguista, a term widely used in the Brazilian political debate, is pejoratively applied to advocates of the free market regime in strategic sectors. The term comes from the notion of handing over (in Portuguese entregar) a state-owned company to the foreign capital.