The humanitarian crisis in Syria is one of the most prominent issues of the international agenda, given the huge amount of people forced to abandon their homes due to the civil war that has been raging the country since 2011. Generically speaking, it is stated that the humanitarian crisis has been triggered by the crackdown of dictator Bashar al-Assad, who has never been indeed willing to dialogue with the opposition. This perspective, although empirically true, is not enough to understand the extension of the problem, which is more multifaceted than it appears to be. In this paper, we will seek to show that the construction of this reductionist Manichean narrative by the United States and their allies in Europe and in the Middle East not only has proved to be misleading, but has also contributed to deteriorate the humanitarian situation by conceding power, tacitly and concretely, to fundamentalist organizations. Furthermore, our goal is to show that the main active governments in the conflict, which helped to increase the flow of expatriates, have been reluctant to shelter war refugees.

The Syrian Civil War is a local outcome of a broader phenomenon in the regional context, the Arab Spring, in which authoritarian governments were impelled to react to mass demonstrations nourished by demands that were as comprehensive as complex. According to the most widespread and heralded narrative by the U.S. government and in large news agencies, the Syrian government, by then, felt pushed by its own people demanding for democratization. From this perspective, Syria would be divided between the oppressive government forces and a pro-democracy opposition taking up arms for a fair cause.

In this view, it was common to distinguish the two main rival groups in the conflict. On one side, the repression forces of dictator Assad sought to suppress any manifestation against the government and to maintain the supremacy of his family, which has been in power in the country since 1971. On the other, the so-called “freedom fighters”, led by the Free Syrian Army (FSA), aimed to overthrow a despotic government, increasing support from public opinion. Thus, as Assad intensified repression to contain the internal pressures, groups willing to use weapons to overthrow him prospered, on the grounds of establishing democracy in the country. Indeed, soon it became clear that the assessment on Assad was justified, as his government did not avoid resorting to the most violent measures to suppress opposition, fostering a broad movement of internal and external displacement of the Syrian population.

However, contrary to what might seem, the situation in Syria could never be simplified to a dichotomy between an authoritarian regime and its democratic opponents. In fact, the Free Syrian Army was overrated by international analysts, both in terms of size and commitment to defend democracy. It soon became evident that this group was much smaller than announced and that its members controlled sparse and tiny regions. In addition, fundamentalist organizations such as Al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State (Daesh) were, in reality, the main opponents of Assad, thus weakening the hypothesis that if the Syrian President was deposed, democratic institutions would quickly flourish. Despite these issues, the United States and its allies in Europe and in the Middle East — including France, the UK, Turkey and Saudi Arabia — have remained faithful to the idea that it was necessary to remove Assad in order to end the civil war and to start a coalition government.

The unyielding stance of the United States proved to be decisive for the continuity of the conflict in Syria as it gave, in practice, “green light” for al-Nusra and Daesh, which were advancing by leaps and bounds. Under the guise of defending the moderate rebels, the anti-Assad fundamentalists were given a “blind eye”, hoping that their victory would strengthen the FSA. However, the result was the opposite: the success of fundamentalists further depleted the ranks of the FSA. Given the fact that many of the fighters who switched sides had been trained by the United States, we observe not an advance of democratic groups, but rather the strengthening of the fundamentalists, who have been relying on U.S. weaponry. Thus, pessimism among Syrian citizens increased, as they no longer hoped for a quick end to the civil war and were forced to flee not only from the government, but also from the al-Nusra and the Daesh.

We note, therefore, that those countries that consider Assad’s fall as a primary goal for Syria not only have failed to promote democracy, but have also toughened fundamentalist movements, thus intensifying pressure on the Syrians, who found themselves forced to leave their country. Probably the situation would have been even worse if the UN Security Council had approved a military intervention in Syria, as wished President Barack Obama in 2013. This initiative would have been tragic for the country’s population, given the fact that most of its inhabitants live in areas under Assad government’s control. The purpose of Obama, ultimately, was to bomb the most populated areas of Syria, which would likely increase the number of refugees and contribute to the expansion of the territory controlled by Daesh and by al-Nusra and even to strengthen popular support for such groups.

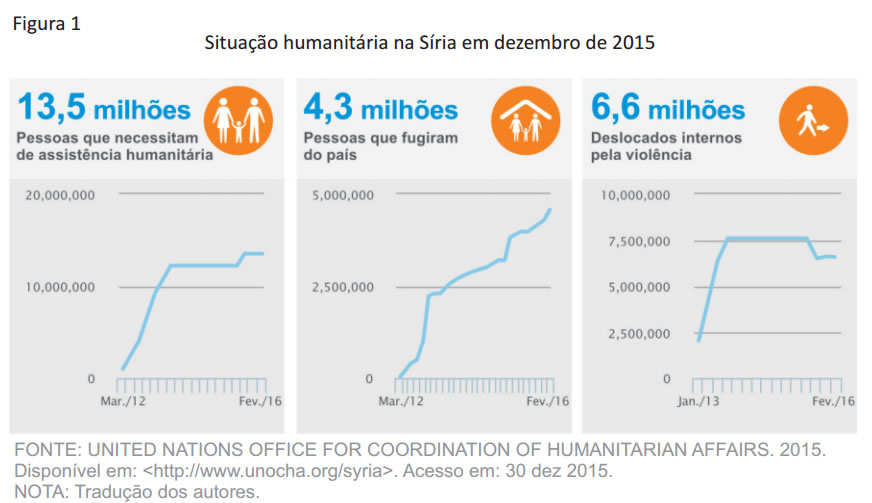

One of the central features of the Syrian crisis is the high number of people driven from their homes, around 11 million people by December 2015, according to the High Commissioner of the United Nations for Refugees (UNHCR) [1], representing almost half of the national population at the beginning of the conflict in 2011. The majority remained in Syria (6.6 million), while the number of refugees in other countries was around 4.3 million. Nearly 90% of the refugees in other countries have moved to the neighboring nations of Syria, notably Turkey (about 2.2 million, or nearly half of all refugees abroad), Lebanon (about 1.2 million, representing an increase of nearly 30% the population of that country), Jordan (630,000), Iraq (250,000) and Egypt (130,000). A share of just over 10% of Syrian refugees abroad has sought protection in Europe, especially in Serbia (275,000) and Germany (185,000).

Germany’s position in relation to the refugees has been dubious and irresolute. In August 2015, the German Government announced that it would no longer apply the Dublin Agreement, under which asylum seekers in the European Union (EU) must remain in the country through which they entered. In practice, the treaty is a burden on the poorest states of the continent — the main gateway for refugees — and allows rich countries to deport migrants who reach their territory. Paradoxically, however, Germany has proposed, within the EU, a package of €3 billion to Turkey in order to contain refugee flow into Europe. Between the lines, it was inferred that a “favorable” conduct of Turkey could accelerate its membership process into the EU. To make matters worse, in November, Germany announced that it would enforce the Dublin Agreement again, burying the hopes that the country would lead a policy of open doors to Syrian refugees.

It is significant that, with the important exception of Turkey, several countries that have been actively involved in the conflict are not among the main receivers of war refugees, in particular the United States, which sheltered only 2,234 Syrian refugees until December 2015[2]. France has received 8,894 refugees[3], while Russia has welcome, officially, about 2,000 Syrian citizens in this condition in its territory[4]. Iran has limited itself to providing material assistance without registering significant incursions of Syrian refugees in its territory. The Gulf monarchies, some of which are crucial supporters of several rebel groups opposed to Assad, have been even more reluctant to receive refugees. Leaders of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE have limited themselves to extend the residence period for Syrian nationals already established in those countries[5]. This phenomenon is serious not only due to the participation of these monarchies in the conflict, but also because they are the countries of the region that exhibit the best financial conditions for hosting the refugees.

After four years of civil war, the outlook for Syria and its refugees remains adverse, to the extent that most of the country’s territory remains under the control of fundamentalists, although the most densely populated regions remain under the firm grip of Assad. Moreover, the absence of a feasible democratic alternative to Assad’s government intensifies the obstacles for stability in Syria, because the U.S. and its allies, although not offering a solution, insist on a regime change in that country, without bearing the costs involved in the intake and assistance regarding war refugees. Under such circumstances, there is an impasse, as the government and the fundamentalists are the most significant political forces in Syria, meaning that it is hard to fight them simultaneously. Indeed, Syria shows that the confrontation with the local government has not fostered a democratic solution, but rather generated a power vacuum that is quickly filled by fundamentalists, just as happened in Iraq and Libya. This scenario is detrimental to the Syrian population, who has little choice but to swell the contingent of refugees.

[1] UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES. 2015 UNHCR country operations profile — Syrian Arab Republic. 2015. Retrieved from

[2] UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Department of State. Myths and Facts: Resettling Syrian Refugees. 2015. Retrieved from

[3] UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES. Europe: Syrian Asylum Applications. 2015. Retrieved from

[4] Россия приютила 2 тысячи беженцев из Сирии. Газета.Ру. 2015. Retrieved from

[In English: Russia has sheltered 2,000 refugees from Syria. Gazeta.ru.]

[5] MARTINEZ, M. Syrian refugees: which countries welcome them, which ones don’t. Retrieved from <http://edition.cnn.com/2015/09/09/world/welcome-syrian-refugees-countries/> on Dec. 30, 2015.