The shipbuilding and offshore industry is a complex comprising a set of linkage activities over an extended period of time for planning (engineering and contracting) and for the assembly of a final product of high added value. Historically, for military or civilian objectives, the shipbuilding industry has a relatively low internationalization level, where, hierarchically, a great diversity of national structures, different ways of organizing the competition and all sizes of companies coexist.

Although it can be considered mature in terms of technology, the marine and offshore industry has been the subject of continuous evolution in production processes in recent decades. Most of these changes are associated with the pursuit of productivity gains related to the evolution of cutting structures and to the pre-treatment of plates, to the building blocks, to the cargo transport, to the increasing automation of several of these steps and to the expansion of the infrastructure of shipyards, bigger and further rationalized (sheds, dams, logistics for the movement and for the internal control of the shipyard, automation, etc.). Compliance with the delivery time and the quality of the final product constitute significant competitive advantages for leading shipyards and reinforce the importance of innovations in the production process[1].

The competitive investment in the naval and offshore sector — the construction of shipyards, the development of engineering and construction companies and local suppliers — requires large amounts of capital with long-term maturity and a relatively stable demand for a long term. In addition to the amortization of the investment and to the necessary capital accumulation for a typical cyclical industry, associated to trade and to global production, this continuity is important for the cumulative technological learning, both in terms of internal processes to the shipyards and in relation to the management of the production chain.

Among the major world producers, the overcoming of barriers to entry in the sector was carried out with broad and diversified stimuli and planning policy, and state productive action, and also through the use, in an initial period, of competitive advantages in the costs of raw materials such as steel and labor (cheap and skilled). These policies allowed the entry of these countries in the sector and the development of national players, stimulating the generation of high added value in a sector with ample productive and technological linkages. In addition to the macroeconomic benefits and technological development in the various stages of the production chain, we should also note the ability of the shipping industry to introduce competition in infrastructural sectors such as transport and energy. These sectors, while creating horizontal incentives, benefiting various segments through the possibility of greater organization in the transport infrastructure, also enable specific competitive advantages that leverage other accumulation strategies, such as the offshore oil producing countries’ industry.

The historical context of the shipbuilding industry can be presented through the leadership alternations over the decades, with the United States and Europe being overtaken by Japan in the twentieth century, South Korea surpassing Japan between 1980 and 1990, and China getting closer to the Korean leadership in the 2000s. Overall, the use of cheap labor matches historically with directing policies for national orders (oil, ship owners and marine), with public financing and the promotion of local businesses in all leading countries. These same features can be found in other cases, such as the shipbuilding industry of Singapore, Norway — leaders of the offshore segment — as well as in the cases of the emerging countries Vietnam and India.

In the first decade of the 2000s, which was extremely vigorous for the shipbuilding industry worldwide, the two main vectors that can be highlighted as central to the expansion of investment in this period were the positive scenario for vessels demand and for the strengthening of national policies for the development of the shipbuilding industry in a larger set of countries, especially facilitated by the growing market itself and the geographic redirection of demand. In this context, the growth of trade, the value of freight, the oil prices and the participation of developing countries in the activity, especially China, have boosted demand for vessels worldwide[2].

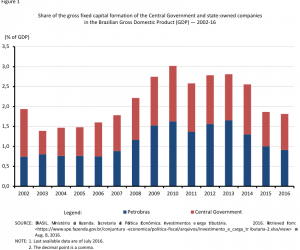

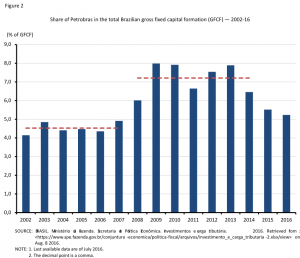

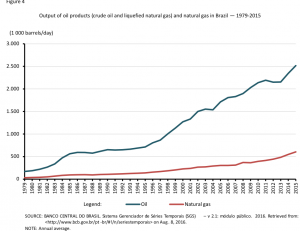

In Brazil, this evolution of the oil industry enabled great advances in the volume of investment and in the modernization of the national offshore production equipment industry. Recent changes in the shipping industry as well as its limitations are directly associated with the volume and profile of Petrobras’ investments and its evolution over the past few years, especially when compared to the previous decades. Institutional changes and the industrial policy of the Brazilian oil and gas industry also fulfilled a decisive role in this evolution. Thus, the 2000s in Brazil were characterized by the vigorous process of the rise of investment in exploration and production (E&P), by intensifying a strategy of driving the demand towards the domestic suppliers and by the progressive structuring of policies and institutions focused on growth and competitiveness of the offshore domestic production. Since the beginning of this period, the signaling of an increase in the amount of orders to the country was accompanied by the completion of contracts with domestic shipyards. This process, in the case of the offshore industry, also presented the expansion of local content in the bidding rounds of the National Petroleum Agency (ANP) as an important transformative element of the productive structure.

Such a scenario was responsible for a movement towards the recovery of the production capacity of the Brazilian offshore industry, which took place in parallel to the resumption of orders for tankers (and, to a lesser extent, cargo ships and container ships), stimulated by Petrobras’ Modernization and Expansion of the Fleet Program (Promef). This increase in demand was at the center of the transformation of the productive structure, which has undergone a recovery of idle structures and subsequently began a stage of expansion and consolidation, with the emergence of new players and shipyards. During this second stage, starting at the end of the first decade of the 2000s, not only were there significant improvements in terms of modernization and capacity building of local players, but new challenges have also emerged. Among them, the very rapid growth of the sector and the need to accommodate the implementation of major projects to tight deadlines. In addition to the recovery process of the shipbuilding industry, the emergence of new shipyards, designed and built based on Petrobras orders, has been an important innovation that emerged from this recovery. The Rio Grande shipyard is an important example of the offshore industry. Its success prompted further industrial densification in its surroundings, yet at an early stage, besides the consolidated Brazilian naval and offshore industrial deconcentration. The naval and offshore cluster of Rio Grande and its surrounding area are composed of Rio Grande shipyards — ERG 1 and 2, Honorio Bicalho and Estaleiros do Brasil —, and its supply chain is one of the main actors in the recovery of the shipbuilding industry in the country.

In addition to the expansion of the production capacity, the response on the level of employment was significant. Considering only the construction activities of vessels and floating structures in Rio Grande, direct employment volume in platform manufacturing increased from an average of 111 jobs between 2006 and 2009 to 7,479 in 2014 (Figure 1).

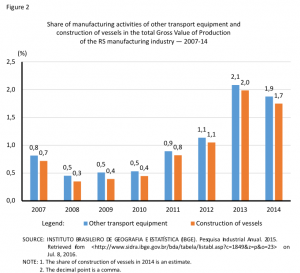

As a result of this expansion, the share of manufacturing activities of other transport equipment in the total Gross Value of Production (GVP) of the state’s manufacturing industry rose from 0.8% in 2007 to about 2% in 2014. Within this sector, the construction of vessels has the largest share, increasing from 0.7% of the total GVP of Rio Grande do Sul’s manufacturing industry in 2007 to approximately 1.7% in 2014 (Figure 2).

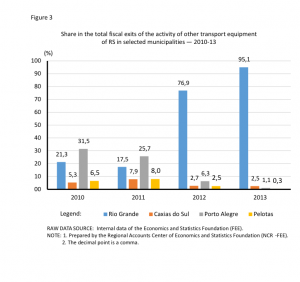

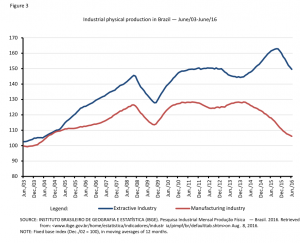

The share of Rio Grande in the total GVP in the manufacturing activity of other transportation equipment of RS, obtained from the value of fiscal exits of municipalities, increased from 21.3% in 2010 to 95.1% in 2013. In this context, this activity increased from 7.4% of the total revenues of the municipality’s processing industry in 2010 to 62.2% in 2013, indicating the importance of the shipbuilding cluster for the city and for the industry of Rio Grande do Sul (Figure 3).

Since 2014, however, the segment as a whole and the shipbuilding and offshore cluster of Rio Grande specifically were hit by the crisis. The fall in oil prices from the middle of that year made the world reduce its demand for ships and floating structures. In Brazil, the progress of the investigations involving Petrobras produced delays in payments, investment decisions and in the expansion of production, which made it impossible or difficult for companies to operate in the sector. The consequences of this crisis were the downsizing of orders and their prices and the employment reduction in the sector. By the end of 2015, considering the peak of employed staff observed in 2013-14, the fall in direct employment in the shipbuilding sector in Brazil was 9,850 jobs, of which 1,730 in Rio Grande (Figure 4). However, if the impacts along the production chain are considered, the reduction of the employment level is much higher.

In addition to the fall in industrial employment, the impacts from the industry crisis have reverberated throughout the economy, as the country has an innovation system for oil production that is highly competitive in some areas. The continuity of this technological dominance in highly knowledge-intensive activities by a group of Brazilian companies would make it possible to shorten their distance in relation to countries that today are at the technology frontier. This fact shows the impact of Petrobras in the Brazilian economy. In this sense, it is important to resume the deepening of technological development and the mastery of knowledge related to the shipping industry and the oil and gas chain, whose range is not restricted to the oil industry, but it has repercussions in other areas of the economy. With the establishment of a new government in May 2016, the prospects for the sector in Brazil and for the shipbuilding cluster of Rio Grande will depend on the conditions of the international oil prices, the direction of industrial policy and the role to be played by Petrobras in this process.

[1] RODRIGUES, F. H.; RUAS, J. A. G. Sistema produtivo 07: perspectivas do investimento em mecânica. Campinas: UNICAMP, 2009. Projeto perspectivas do investimento no Brasil. Bloco: produção. Sistema produtivo: mecânica. Documento setorial: naval. Retrieved from

[2] For more details, see AGÊNCIA BRASILEIRA DE DESENVOLVIMENTO INDUSTRIAL (ABDI). Relatório de acompanhamento setorial: equipamentos de produção de petróleo offshore (Epo): estrutura do setor e perspectivas para o Brasil. Campinas, 2012. Retrieved from < http://www.abdi.com.br/Estudo/000%20-%20neit_EPO_01.pdf > on Jul. 8, 2016.